Warring States Period

Original

Chinese History

Dec 02 • 2393 read

Eastern Zhou Dynasty, from 770 to 256 BC, is divided into two periods, the Spring and Autumn period which lasted from 770 to 476 BC and the Warring States period (from 475 to 221 BC).

/fit-in/0x0/img/201912/Warring_States_Period-article-1575278751.jpg)

China has over 5000 years old history, but since from 221 BCE, it has been considered a unified Nation. Before the China unification, and after the peaceful and philosophical Spring and Autumn Period seven states fought for hegemony, territorial advantage, and dominance which is known as the Warring States period (481/403 BCE – 221 BCE). Much of this period was the second half of the Zhou dynasty under the rule of the Eastern Zhou. It was the Qin state conquered all the other rival states and unified Chinese state under the Qin dynasty. However, besides continuous warfare and countless casualties, the Warring States period saw significant advancement in society, philosophy, agriculture, arts and commerce, and set the foundations for the flourishing of Imperial China. Historians are not agreed upon the starting date of the Warring States period, and some believe its starting point was 481 BCE when the Lu chronicles end while others think the Warring period started in 403 BCE when the Zhou court officially recognized the three states; Zhao, Wei, and Han. Still, other historians chose the starting dates within that period such as Sima Qin; one of the most famous ancient Chinese historians believed the starting point was 475BCE.

The authority of the rulers of the Eastern Zhou dynasty (771-256 BCE) in the 5th century was weak, and they were not able to exert much real power in their own country. They were no longer dominated in army terms, they were crumbling and were forced to depend on the military of other states, who on occasion took the opportunity to forward their own territorial claims. That’s why the Zhou rulers were forced to choose army leader from another state, the military leader of the Zhou army. The chosen commanders from other states had to swear loyalty to the Zhou feudal system, and that’s why they were given the title of Hegemon. Around 100 states had been combined into seven states by 4th century BCE; Zhao, Yan, Wei, Qin, Qi, Han and Chu. Smaller states were there between these big states, but by that time they were so large that it was difficult for the one to absorb another. At that, there was a trend of building long defensive walls and borders, some of which were hundreds of kilometers long made of earth and stones. Some of these walls still exist today, such as the Qi wall located in Mulinnggun in Shandong province which is 4 meters high and 10 meters across in places.

The ruler of each state declared himself king and independent of the Zhou Empire. Each one was looking to expand their area, and that’s why they were often were competing over succession disputes caused by the common policy of intermarriage between different royal families. This competition among states caused continues war among them, which is known by the Warring States period. There were 358 wars between states between 535 and 286 BCE. Commanders led the vast military, and they all were competing for the prize of the victories state, which was the control of a unified China.

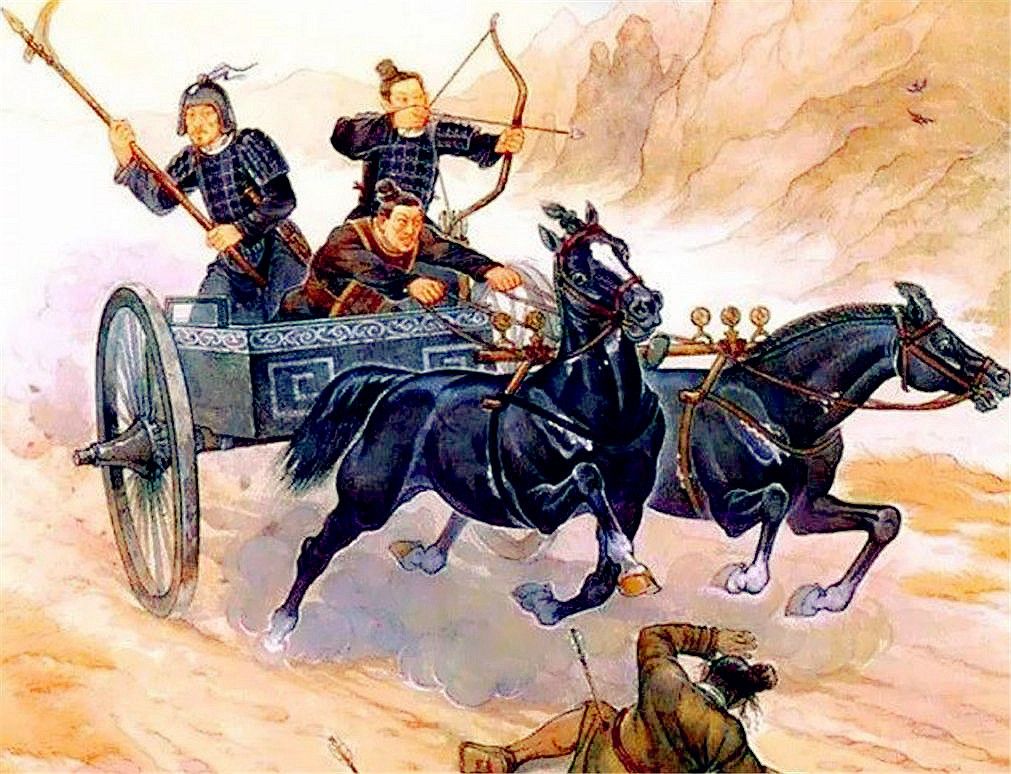

During the Warring States period, the large infantry armies based on universal conscription, the diffusion of iron swords and crossbows made warfare more deadly than in previous times. The battles were more effective because of large numbers of chariots and infantry. The war became more dynamic by training of more disciplined troops and espionage playing their part in victories. Before that time, the scale of the battles was short, and the army’s soldiers were less as compared to 200000 infantry in the Warring States period. The Chu, Qi, and Qin states each possessed a force soldiers close to one million men and a cavalry force of ten thousand. The battles lasted for months and even years with casualties in the tens of thousands. The military of states had to fight on multiple fronts, and their objectives were not only to occupy a new land but to destroy the army capacity of the enemy state.

This continuous warfare heavily affected ordinary people. The invasion of the military destroyed property and crops, males members of the society were expected to fight for the state. The last battle of that period which is called Changping was involved every male from the Qin people whose age was above 15 years. It was difficult for the formers to do farming and avoided military service. Those soldier who was fought well in the war were getting rewards such as in the Qin state if a solider cut the head of the enemy entitled the soldier for promotion and would get 5 acres of land. For every soldier and state, success in war became the only goal. The expectation on the commanders was another development in general warfare. They were longer able to claim a right of command through birth, and they were required to demonstrate their skills of the military. The strategy was necessary on the battlefield, but it became essential in siege warfare when the enemy chose to try and resist attack from within their well-fortified cities or when they protected their borders with watchtowers connected by defensive walls.

The Rise of Qin

The Qin was one of the few states which remained to the Zhou, for instance, one of the rulers of Qin called Duke Xin, was rewarded with the title of Hegemon in 364 BCE for protecting the Zhou interests. Xiao, the successor of Duke Xin, was also rewarded with the same title in 343 BCE. Xiao took the services of the gifted advisor from the Wei state, who recognized the Qin state and made it even more powerful. Population and regions were divided in a way that was more easy to manage, and the collection of taxes was more effective. That was the strength of the Qin now that Zhou king gave a royal status to the ruler Huiwen in 326 BCE. The advantage of the Qin state was that it was located in a protective mountain range and it was on the peripheral states that it had more freedom to expend to the area that was not held by the rival Chinese state. They had a stable government based on the philosophy of legalism, with a local magistrate and officials to help run the provinces and armies.

In 316 BCE the Qin conquered Shu state, this victory over Shu helped the Qin to occupy their productive agriculture lands which further enrich their state. The capital of Chu state also fell under the control of the Qin 278 BCE. The Qin great victory was won against the Zhao state after fighting three years-long battle. The Qin was unstoppable, In 256 CE the Zhou king died, and no one was appointed, at that time Qin conquered the rest of the other states. Qin defeated Han in 230 BCE, Wei in 225 BCE, Zhao in 228 BCE, Chu in 223 BCE. After the victory against Qi and Yan, the Qin state was able to unify the Chinese empire throughout China. The king of Qin, Zheng, awarded himself the title of the first emperor.

The Cultural Developments of Warring States

War, battles, and bloodsheds dominated the Warring States period, but there were some cultural developments too. The need to produce technological advance weapons, better than the weapons of the enemy led to better techniques, tools and craft skills, especially the use of iron and metalworking. Artists were able to produce more skilled artwork, and they master materials such as jade and lacquer, which difficult and time-consuming. A large number of soldiers needed a massive amount of food supplies which were met from the improved agriculture. The use of more land, better tools made from iron and better irrigation system helped to increase agricultural productivity. Cities grew in size; the ruler's palaces became more extravagant, marketplaces expanded, the area dedicated to the industries where goods as weapons and pottery could be mass-produced up.

As new areas conquered and alliances were formed, so too, trade developed and with it a wealthy middle class of state administrators and merchants. Society moved from a strict system where one’s position was defined by birth. Money was introduced in the shape of bronze coins with a distinctive central hole and became known as knife-money. There was now the possibility to acquire status and wealth for those with talent. Thoughts developed too, the wars and battles forced intellectuals to reexamine their views on the world and the role of religion and God in human affairs. Poets and writers attempted to explain and justify the events of the Warring States period and their terrible effects on ordinary people.

The philosophers of the Warring state

Three prominent belief systems; Confucianism, Daoism, and legalism emerged during the Warring States period of Chinese history. Confucianism is a philosophy of social order, moral uprightness, and filial responsibility. Daoism was a philosophy of universal harmony that advised its practitioners not to get involved in worldly affairs. While legalism is a theory of autocratic, harsh sentences, and centralized rules. These three philosophies greatly influenced early Chinese empires while some of the states adapted as official state ideologies.

At the end of the Zhou dynasty, as feudal lords fought over land, there was a government minister and scholar by the name of ‘Kong Fuzi’ later known by Confucius by 16th century Jesuits. Confucius taught the classics; the ancient Zhou-era the book of Changes, the Book of Odes, and Book of Documents through which he gained students and followers. Confucius was mainly concerned about the class of leaders and their ethical and intellectual cultivation. He also wanted to rethink the notion of class, status, and hierarchy in society. The books that Confucius taught were already ancient in Confucius's time. The respect that Confucius gave them is perfectly in-line with his philosophy of filial piety-respect for your parents or elders. In this sense, Confucianism is a philosophy of respect for the past and its traditions. Many of the ideas which are attributed to Confucius had likely already been in circulation in Chinese society. Few of Confucius’s original thoughts survive, The Analects of Confucius, which means his students and followers composed the collected sayings of Confucius based on conversations they had with him.

Confucius urged ethical and upright behavior, framing a responsible government as a moral duty similar to parenthood. He believed that providing an excellent example of moral conduct to the people would spur them to act within the confines of the law. Confucianism stressed the idea that people could be useful if they followed moral instruction and performed rituals that worshipped the gods and honored the ancestral dead. In a time of war and upheaval, the Confucianists believed only careful maintenance of the old traditions could support societal unity. Many Chinese rulers implemented Confucian principles. For instance, Emperor Wu of Han encouraged hierarchical social structures based on Confucian principles, which he believed would bring about greater social harmony throughout Chinese society.

Legalism

Legalism encourages the notion of strict social order and law, and harsh collective sentences, ideas that influenced Qin Shi Huangdi’d centralized rule. If someone wants to understand Legalism, they have to go back to Shang Yang times, who was a reformist statesman during the Qin state. Shang Yang's understanding of humanity was considerably different from that of Confucius. Shang Yang was born in 390 BCE, 169 years before the reign of Qin Shi Huangdi. In The Book of Lard Shang, he recommended harsh punishments for light offenses; he reasoned that if petty crimes were met with heavy sentences, more serious crime would be deterred. Under the Shang Yang government, the people of Qin state had severely constrained lives; peasants could not leave their villages without travel permits; farmers who did not meet growing quotas were forced into slave labor, and minor crimes were punished with severity.

The Qin state weakened the power of its aristocracy and combined power and land under one royal family. This change in the structure of power led the ruler of Qin, rather than feudal lords, to directly control the lives of people. Trade with other states was declined, the law focused on farmer activities, military services, and agriculture. The decline in the power of local aristocrats led to the formation of an administrative system that answered directly to the head of Qin. The administrators, bureaucrats, in such a system, were accountable to the rulers.

In the third century BCE, during the time of King Zheng’s rules, an intense focused on recruiting troops, and increasing agricultural production had turned the Qin state into a military powerhouse. King Zheng began a nine-year campaign to overcome his neighbors. In 221 BCE, when he defeated his enemies, Zheng declared himself Qin Shi Huangdi which means the first Emperor of Qin. The new emperor planned to create an empire-wide administrative bureaucracy modeled based on his home state. China was divided into regional administrative zones, under the watchful eyes of Qin Empire officials. Under Qin Shi Huangdi, ordinary people were recruited into forced labor and punished or disfigured for petty infractions.

Daoism

Confucianism and legalism both required strict obedience to principles, whether they were enforcement-based legalist one or shame-based Confucian Ones. In contrast, Daoism recognizes no law but the Dao, or the way. In the book called Dao De Jing, Laozi; the founder of Daoism explain Dao means; the one who knows the Dao does not speak, the one who speaks does not know the Dao. The intelligent man shuts his mouth and closes his gates. In this way, the Dao was often labeled as resilient to description or definition; a nameless, shapeless, but also a creative force in the universe. This may appear like a contradiction, but it makes sense when we consider the fact that Daoism is a kind of anti-activism; it asserts that the best life is one of willful ignorance, seeking no knowledge and avoiding involvement in politics or public life.

Daoists were not convinced that governments could generate harmony and social order. Instead, they concentrated their attention on individual behavior and the ways it might be adapted to be in harmony with the Dao. The Dao is intended to characterize the natural order of the universe, and Daoism instructs that human beings are the only species that violate the Dao. Rather than pursue to raise oneself through words and deeds, Daoists cultivated a practice of Wu Wei, giving in to thoughtless, effortless, and natural action.

The Dao is not a goal to vigorously pursue, but rather a state to be approached through not approaching it. Daoism believes that rather than involve yourself with affairs of state, it is better to keep your lives and actions simple. Silence is appreciated above words; inaction and stoicism appreciated the above action and outrage. Daoism believes that if all people ceased striving for glory, attainment, and riches, there would be no enemy, no war, and lesser suffering. Daoism philosophy influenced many elements of later Chinese philosophy, especially Chinese Buddhism.

Confucianism, Legalism, and Daoism all played a role during the Warring States period. These three influenced the styles of the Chinese government throughout the Qin ascendancy, the Han dynasty, and beyond, becoming more or less influential depending on which dynasty and power. They also heavily influenced social structures.

Tours of the Warring States Period Sites

The Terracotta Warriors and other sites in Xi’an Province are the places to learn about the Qin state and Qin Dynasty. The Hubei Provincial Museum in Wuhan has the most extensive collection of artifacts from the Warring States period. Also visit the Museum of the Zhou Imperial Carriages in Luoyang, Zhou Dynasty Capital in the Warring States period.

Responses • 0

0/2000

ID: 322

Matthias

Offline

Oct 10

Visited

From

Hafizabad, Pakistan

Send Message

Related

Spring and Autumn PeriodChinese idiom - 贪小失大, it means covet a little and lose a lot, this is a metaphor for seeking immediate benefits over long-term ones, seeking small profits but losing big profits.

- - - - - -

战国时期,蜀国国君生性贪婪,秦王听说后想讨伐他。但是通往蜀国的山路深涧十分险峻,军队没有路可以通往蜀国。

In the warring States period, the king of Shu was greedy, so the king of Qin want to occupy the Shu state. But the mountain road to the Shu state is very steep, the army has no way to the Shu.

秦王的谋士想到一条计策,说秦国发现了有一头能下金粪的石牛,并且想把这头牛送给蜀王。

A counselor to the king of Qin thought of a scheme, said they found a stone cow that could lay gold manure and wanted to give the cow to the king of Shu.

蜀王听说秦王要送给自己一头能下金子的牛,不觉得有奇怪和危险,反而非常高兴。于是他下令民工开山填谷,铺筑道路迎接石牛。

The king of Shu heard that Qin wanted to give himself a cow that could lay gold, not to feel any strange and dangerous, but very happy. So he ordered the migrant workers to open the mountain to fill the valley and pave the way to meet the stone cattle.

但是,秦王率领军队紧随石牛的后面,从而导致蜀国毁灭,蜀王也死了。

However, Qin led the army to follow the stone cow behind, which led to the destruction of the Shu, and the king died.

人们嘲笑蜀王是贪小利而失大利。

People derided the king of Shu, as greedy for small profits but losing big profits.

- - - - - -

HSK 1

不

高兴

和

后面

了

没有

是

说

他

想

有

这

的

HSK 2

非常

觉得

可以

路

要

也

HSK 3

把

发现

奇怪

自己

HSK 4

并且

十分

死

危险

于是

HSK 5

从而

导致

反而

时期

迎接

HSK 6

嘲笑

毁灭

军队

率领

贪婪Word order for the duration of time: how long someone did something.

The word order for expressing the length or duration of time is very different from expressing the time when an action occurred.

Here, the length of time of action can come at the end of the sentence, whereas this can NEVER happen with expressing WHEN something occurred.

I slept for eight hours of sleep.

Wǒ shuìle bāge zhōngtou (xiǎoshí) de jiào.

我睡了八个钟头 (小时) 的觉。

OR, if you are stating the length of time you spent on various activities, in addition to sleeping: I slept (for) eight hours.

In terms of my sleeping, I slept eight hours.

Wǒ shuìjiào shuìle bāge zhōngtou (xiǎoshí).

我睡觉睡了八个钟头 (小时)。

Once you’ve established sleeping as your topic of conversation, then you can, of course, simply say, as we would in English:

I slept for eight hours.

Wǒ shuìle bāge zhōngtou (xiǎoshí).

我睡了八个钟头 (小时)。

Yesterday, I studied for five hours.

Yesterday, I studied five hours of books.

Zuótiān wǒ niànle wǔge zhōngtou (xiǎoshí) de shū.

昨天我念了五个钟头 (小时) 的书。

OR, if you’re enumerating the relative amount of time you spent doing various things yesterday: I studied for five hours yesterday.

Yesterday as for my studying, I studied (for) five hours.

Zuótiān wǒ niànshū niànle wǔge zhōngtou (xiǎoshí).

昨天我念书念了五个钟头 (小时)。

And once we've established "studying" as the topic of discussion, then we can simply say, as in English:

I studied (for) five hours.

Wǒ niànle wǔge zhōngtou (xiǎoshí).

我念了五个钟头 (小时)。

HOWEVER, when a length of time is given in a sentence with negation, bù 不 or méi/méiyǒu 没/没有, then the period of time comes BEFORE the verb:

English: I haven't slept for two days.

Chinese: I for two days have not slept.

✔ CC: Wǒ liǎngtiān méi shuìjiào le.

我两天没睡觉了。

✖ BC: Wǒ méi shuìjiào liǎngtiān.

我没睡觉两天。

Literally: I haven't slept for two days.

English: I haven't smoked for a year.

Chinese: I for one year have not smoked.

CC: Wǒ yìnián méi xīyān le.

我一年没吸烟了。The word polo is thought to derive from the Tibetan pulu, the wood from which the ball was made.

Much controversy surrounds the origin of polo. Tibet, China, Iran, India, and Central Asia have all been proposed as homelands for the game. It remains possible that the game had more than one point of origin, though a recent study has argued convincingly that polo developed in northeastern Iran out of the equestrian chase games played by the mounted nomads of Central Asia in the last centuries before the Common Era.

Polo probably was introduced to China sometime between the end of the Han period (206 B.C.E.- 220 C.E.) and the early part of the Tang dynasty (618-907). It seems likely that it was introduced by the Xianbei tribes that controlled northern China from the fourth to the sixth century. The ruling house of the Tang dynasty, the Li family, itself had Xianbei ancestry, at least on the maternal side. The Xianbei, because of their nomadic origins, had a great fondness for horses, a trait that (like many aspects of their culture) was inherited by the Tang dynasty. It is also notable that the Xianbei accorded higher status and more physical freedom to women than the Han Chinese, so women became avid polo players under the Tang dynasty.

The emperors of the Tang dynasty such as Zhongzong, Xuanzong, Muzong, Jingzong, Xuanzong, Xizong, and Zhaozong were all supporters and participants themselves in the polo sport. In the 6th year of the Tianbao era (747), Emperor Tang Xuanzong issued a special order and declared that polo would become one of the subjects for military training.

Polo was wildly popular during the Tang dynasty but it was also dangerous; riders thrown from their horses were frequently injured or killed. So sometimes donkeys were used instead of horses - as a safer alternative.

Tang dynasty women playing polo, paintings by Wang Kewei.30个疫情高频词汇

新型冠状病毒

novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV)

肺炎

pneumonia

新型冠状病毒感染的肺炎

novel coronavirus-caused pneumonia

确诊病例

confirmed case

疑似病例

suspected case

重症患者

patient in critical condition

病死率

fatality rate

密切接触者

close contact

接受医学观察

be under medical observation

隔离

quarantine

潜伏期

incubation /ˌɪŋkjuˈbeɪʃn/ period

人传人

human-to-human transmission

飞沫传播

droplet transmission

发热、咳嗽、呼吸困难

fever, cough, and difficulty in breathing

急性呼吸道感染病状

acute infection symptom

输入性病例

imported case

输入性病例:指来自疫情流行区的病例,也称一代病例

二代病例

secondary infection case

二代病例:指被一代病例感染的本土病人

隐性感染

asymptomatic /ˌeɪsɪmptəˈmætɪk/ infection

隐性感染:指感染了病毒,但无明显症状的病例

疫情防控

epidemic prevention and control

口罩

(face) mask

防护服

protective clothing/suits

护目镜

goggles

一次性手套

disposable gloves

医疗物资

medical supplies

疫苗

vaccine

国际关注的突发公共卫生事件

Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC)

封城

the lockdown of a city /

a city is on lockdown

应急医院

makeshift hospital

重大突发公共卫生事件一级响应

first-level public health emergency response

国家卫生健康委员会

National Health Commission (NHC)Election Words

选举 - XuǎnJǔ - election

选举程序 - XuǎnJǔ ChéngXù - electoral procedures

选举大会 - XuǎnJǔ DàHuì - election meeting

选举规则 - XuǎnJǔ GuīZé - election regulation

选民 - XuǎnMín - voter/elector

被选举权 - BèiXuǎnJǔQuán - right to be elected

补缺选举 - BǔQuē XuǎnJǔ - supplementary election

筹款 - ChóuKuǎn - to raise money

出奇制胜 - ChūJī ZhìShèng - to outflank someone

初选 - ChūXuǎn - primary election

当选 - DāngXuǎn - be elected

法定程序 - FǎDìng ChéngXù - due course of law

法定人数 - FǎDìng RénShǔ - quorum

废票 - FèiPiào - invalid vote/voided ballot

否决权 - FǒuJuéQuán - veto power

副总统 - FùZǒngTǒng - vice president

改选 - GǎiXuǎn - re-election

个人投票 - GèRén TóuPiào - individual vote

公开投票 - GōngKāi TóuPiào - open vote

合格选民 - HéGé XuǎnMín - eligible voter

候补者 - HòuBǔZhě - alternate candidate

候选人 - HòuXuǎnRén - candidate

极端派 - JíDuānPài - radical

计票 - JìPiào - count of votes

记名投票 - JìMíng TóuPiào - disclosed ballot

监票员 - JiānPiàoYuán - ballot examiner

竞选纲领 - JìngXuǎn GāngLǐng - manifesto

竞选活动 - JìngXuǎn HuóDòng - election campaign

决定性票 - JuéDìngXìng Piào - decisive vote

抗议票 - KàngYìPiào - protest vote

拉票 - LāPiào - soliciting votes

连任 - LiánRèn - continue in office

领先者 - LǐngXiānZhě - front runner

落选 - LuòXuǎn - lose an election/be voted out

民意调查 - MínYì DiàoChá - opinion poll

普选 - PǔXuǎn - general election

全民投票 - QuánMín TóuPiào - Referendum

提名 - TíMíng - nominate

提名者 - TíMíngZhě - nominator

投票 - TóuPiào - cast a ballot

投票率 - TóuPiàoLǜ - turnout

投票日 - TóuPiàoRì - polling day

温和派 - WēnHéPài - moderate

压倒性胜利 - YāDǎoXìng ShèngLì - landslide victory

摇摆/中间选民 - YáoBǎi/ZhōngJiān XuǎnMín - swing voter

摇摆州 - YáoBǎi Zhōu - swing states

一场恶战 - Yī Chǎng ĚZhàn - uphill battle

鹰派人物 - YīngPài RénWù - hawk

右翼人士 - YòuYì RénShì - right winger

在位者 - ZàiWèiZhě - incumbent

在野党 - ZàiYěDǎng - opposition party

造势活动 - ZàoShì HuóDòng - campaign rally

争取连任 - ZhēngQǔ LiánRèn - stand for reelection

政党 - ZhèngDǎng - political party

执政党 - ZhíZhèngDǎng - ruling party

总统 - ZǒngTǒng - president

左翼人士 - ZuǒYì RénShì - left winger百(baiˇ) 100

一+白(baiˊ)=百, Talk a lot

、+曰=白, 曰(Yue) it's the tongue swinging when speaking, Add a point emphasis to speak, to make things clear is 白, the cleanest color is white

千(Qian) 1,000

People's thighs are restricted, this is slave, many slaves are 1,000

萬(Wanˋ) 10,000

Scorpion

Scorpions are social animals. Many scorpions appear when they enter the mating period, which is very scary.

億(yiˋ) 100,000,000

音+心=意(yiˋ), 音(Yin) is sound,心(Xin) is heart, the sound in your heart

When a people (憶)remind have a lot of sound in heart

人+意=億

兆(Zhaoˋ)1,000,000,000,000

Crack

Ancient sorcerer burns tortoise shell, watching the cracks for divination, omen of heavy rain or big events, mean a huge number

零(Lingˊ) 0

雨(Yuˇ)+3口(Kouˇ)+令(Lingˋ)

雨 is rain, 口 is the mouth, 令 is order, During the drought, many(three) wizards chanted spells and prayed for rain. Mean very less rain, Have not three mouth now立 夏 The Beginning of Summer

今天到来一年二十四节气中的第七个、十二节令中的第四个,称为立夏。立夏送走了春季,开始了夏天。立夏给我们带来了温暖或炎热,带来通常更为频繁的雨水,昼夜温差减小。太阳常照当头,人们常忍受炎热之苦。夏季是最繁忙的季节之一,夏收夏种六月上半月之中,每年的高考也在此时进行,偶尔有例外。六月一日是国际儿童节,七月一日是党的生日,八月一日是建军节。节日连至使全国人民更忙乎。

Today comes the 7th solar term of the 24’s and also the 4th seasonal periodical of the 12’s of the year. It is termed as the Beginning of Summer, sending off the spring and starting a new season, summer. It brings to us warmth or heat, with the difference of length between day and night getting less and rainfall usually more frequent than ever. The sun for a period shines over head with people suffering constant heat. Summer is one of the busiest seasons of the year, with the summer harvest and summer sowing on the way in the first half of June as well as the yearly college entrance examinations held, but occasionally not. Hence June is a month of importance. This season is full of festivals with June 1st, Children’s Day, July 1st, the Party’s Birthday, and August 1st, the PLA’s Birthday. Celebrations of them make people throughout the country even busier.Must-Read for the Year of the Snake: Snake-Related Idioms and Stories Packed with Wisdom and Inspiration!

As we approach the Year of the Snake in 2025, we’re gearing up to embrace a year brimming with agility and wisdom. In Chinese culture, the snake has a deep historical significance and rich symbolism, giving rise to many idioms and stories. These idioms not only carry profound wisdom but also offer valuable lessons for modern life. Today, let’s dive into some of these snake-related idioms and the tales behind them.

Adding Legs to a Snake (画蛇添足)

Meaning: Doing something unnecessary that ends up ruining the original effort.

Origin: From *Strategies of the Warring States*. In ancient Chu, after a ritual, the host offered a pot of wine to his guests. Since there wasn’t enough for everyone, they decided to hold a drawing contest: whoever finished drawing a snake first would win the wine. One man finished quickly but, seeing others still working, arrogantly added legs to his snake. By the time he was done, someone else had already won the wine.

Lesson: Know when to stop. Overdoing things can backfire.

Startling the Snake While Beating the Grass (打草惊蛇)

Meaning: Acting carelessly and alerting the opponent, giving them a chance to prepare.

Origin: From *Recent Events of Southern Tang*. During the Tang Dynasty, a corrupt official named Wang Lu was reviewing legal documents when he came across a petition accusing one of his subordinates of misconduct. Panicked, Wang Lu scribbled on the petition: “Though you beat the grass, you’ve startled the snake.” He meant that while the accusation targeted his subordinate, he himself felt threatened—just like how beating the grass would scare a hidden snake.

Lesson: Proceed with caution and avoid tipping your hand too soon.

Mistaking a Bow’s Reflection for a Snake (杯弓蛇影)

Meaning: Being overly suspicious and fearful due to misunderstandings or illusions.

Origin: From *The Book of Jin*. During the Jin Dynasty, a man named Yue Guang hosted a banquet. One guest thought he saw a snake in his wine cup but, not wanting to cause a scene, drank it anyway and left in a hurry. Days later, feeling unwell, he confessed his fear to Yue Guang. Yue Guang realized it was just the reflection of a bow on the wall. He invited the guest back to prove it, and the guest’s fears—and illness—vanished.

Lesson: Stay rational and don’t let illusions cloud your judgment.

Feigning Compliance (虚与委蛇)

Meaning: Pretending to go along with something while being insincere.

Origin: From *Zhuangzi: Responding to Emperors and Kings*. During the Warring States period, Liezi introduced a famous diviner named Ji Xian to his teacher, Huizi. Huizi pretended to show different attitudes each time, making it impossible for Ji Xian to read his true intentions. Eventually, Ji Xian fled in fear. This story illustrates the idea of “feigning compliance”—pretending to cooperate while actually being evasive.

Lesson: While flexibility can be useful, honesty and authenticity are far more important.

Ox Ghosts and Snake Spirits (牛鬼蛇神)

Meaning: Describing people who engage in strange, unethical, or shady behavior.

Origin: Originally referring to mythical monsters, this phrase later came to describe people with questionable morals or dubious actions. It’s often used to criticize negative social phenomena.

Lesson: Be careful who you associate with. Stay away from those with poor character and uphold your integrity.

Even a Strong Dragon Can’t Crush a Local Snake (强龙不压地头蛇)

Meaning: Even the most powerful individuals may struggle against local forces.

Origin: From *Journey to the West*, Chapter 45. When Tang Sanzang and his disciples arrived in Chechi Kingdom, they clashed with a fake Taoist priest, Tiger Strength Immortal, who was challenged to summon rain. Sun Wukong, knowing that “even a strong dragon can’t crush a local snake,” let the priest try first. Sun Wukong secretly persuaded the gods to ensure the priest’s failure. This idiom often describes how outsiders may find it hard to overcome local powers in unfamiliar territory.

Lesson: Respect local customs and power dynamics to avoid unnecessary conflicts.

A Snake Trying to Swallow an Elephant (人心不足蛇吞象)

Meaning: Describing insatiable greed and excessive ambition.

Origin: During the reign of Emperor Renzong of Song, a poor woodcutter named Wang Wang found an injured snake and nursed it back to health. The snake brought joy to Wang and his elderly mother. Later, when the emperor sought a night pearl, the snake offered one of its eyes as a gift, and Wang was made prime minister. When the princess fell ill and needed the liver of a thousand-year-old python, Wang asked the snake again. Reluctantly, the snake allowed Wang to enter its belly to retrieve the liver, but Wang was swallowed whole. Thus, the saying “a snake trying to swallow an elephant” became a cautionary tale.

Lesson: Contentment is key. Excessive desires can lead to ruin.

Once Bitten by a Snake, You Fear a Rope for Ten Years (一朝被蛇咬,十年怕井绳)

Meaning: A past trauma can make someone overly cautious or fearful of similar situations.

Origin: This idiom comes from a folk saying. It refers to someone who, after being hurt once, becomes overly fearful of anything resembling the source of their pain. For example, someone bitten by a snake might fear even a rope, mistaking it for a snake.

Lesson: While it’s important to learn from past experiences, don’t let fear of the past dictate your future.

The snake symbolizes wisdom and courage. In the Year of the Snake 2025, let’s take these lessons to heart:

- Know when to stop (Adding Legs to a Snake).

- Act cautiously and avoid revealing your plans (Startling the Snake While Beating the Grass).

- Stay rational and don’t let illusions mislead you (Mistaking a Bow’s Reflection for a Snake).

- Be sincere yet adaptable (Feigning Compliance).

- Be content and avoid excessive ambition (A Snake Trying to Swallow an Elephant).

Wishing everyone a prosperous and successful Year of the Snake!

May the wisdom and courage of the snake guide us to greater achievements and joy in the year ahead!Sunny

✅ 10+ years of rich teaching experience

✅ Teaching Certificate and Mandarin Test Certificate

✅ Broadcasting DJ

✅ Standard Pronunciation

✅ The most advanced learning methods

✅ Teach language with Chinese culture

【Ace course】

✅ Pinyin ✅ Speaking✅ Speech✅ Reading✅ Chinese Culture

Hi,everyone! I’m Sunny.

I have ten years of experience in teaching Chinese as a foreign language. I have helped a number of foreigners to improve their Chinese proficiency and learn Chinese culture, and I have been unanimously praised and affirmed. I have also taught Chinese in public school for some time, and I have been very popular with students. In addition to my mother tongue being Mandarin, I’m also professional in English.

Besides, I have a wide range of interests and learning.I am very passionate about traditional Chinese culture, as well as traditional Chinese medicine, Chinese calligraphy, Chinese painting,psychology, recitation, broadcasting, music and so on. I am looking forward to discussing and sharing with you in my class. In addition to language teaching, I will also teach Chinese culture in class, such as Chinese classics, Chinese medicine, Chinese classical music, paper cutting, hand waving,etc, so that you can understand the whole China. While learning the language, you can also learn the ideas, wisdom and culture behind the language.

Most of my students are from the United States, Canada, Britain and Australia, including adults and children. Whether it’s 1V1,1 V many, online or off line,I have rich teaching experience to help you improve your listening, speaking, reading, writing and translation in Chinese easily and efficiently, and help you learn more about Chinese culture. My students like me very much. On average,every student has studied Chinese with me for nearly two years and has made great progress.

It’s very interesting in my class. I will adopt situational teaching and task-based teaching and connect language learning with your daily life, making Chinese learning life-oriented and teaching language in the contexts,situations, games and activities.I will enable you to learn Chinese more efficiently and happily in the relaxed atmosphere, making Chinese learning fun and interesting and making you fall in love with Chinese and Chinese culture. I advocate immersion teaching and I hope my students can be immersed in all Chinese teaching atmosphere, obtaining happiness,wisdom and growth in my class.

I believe I will be the teacher you are looking for and I will help you find the most suitable and efficient way to learn Chinese. Hope that I can be the best Chinese teacher and your best friend in life, helping you realize your dream. Look forward to meeting you in the class. I believe we will feel as old friends.

Book my trial class quickly! I can’t wait to see you...