Green Tea

Original

Chinese Tea

Feb 10 • 668 read

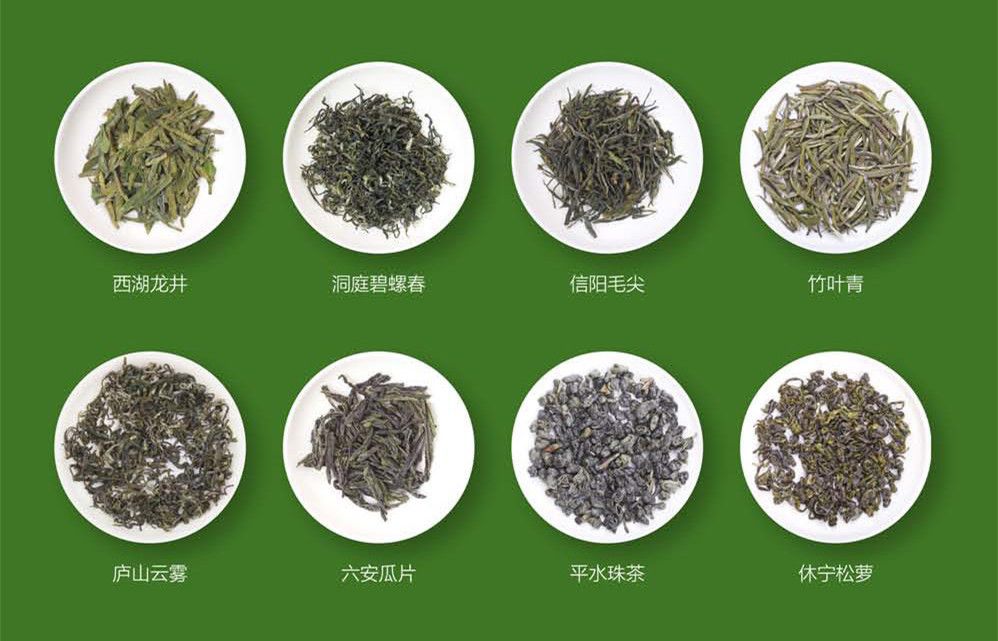

Green tea, as unfermented tea, is least processed and closest to its natural state. 4 famous green tea are: DRAGON WELL 龙井, GREEN SPIRAL 碧螺春, MOUNT MENG SWEET DEW 蒙顶甘露, and BAMBOO LEAVES GREEN 竹叶青.

As unfermented tea, finished green tea requires the least processing and is the closest to the tea leaf in its natural state. The tea brewing process is almost like watching time move backward: the green leaves unfold within the verdant liquid until they seem as fresh and alive as if still they were on the branch.

Differences in the production of various green tea lie principally in the way fixation and drying are carried out. Japanese green tea, for example, retains the ancient Chinese method of steaming. Processed tea leaves that have been steamed take on a dark green tint, while the liquor is vibrantly green, similar to pigments used in painting, and the aroma is faintly musty.

There are three principal types of tea in today's China: those that undergo stir fixation (pan-fried) such as Dragon Well, Green Spiral and Bamboo Leaves Green (Zhi Ye Qing); baked types such as Mount Yellow Fuzz Tip (Huangshan Maofeng), Liu’an Leaf (Liu’an Guapian) and Taiping Monkey Chief (Taiping Houkui); and sun-dried, mainly Yunnan Green Tea, and the raw (“un-ripened”)tea leaves incorporated in pressed Pu-erh.

These three fixation and drying methods used in Chinese green tea ensure that each type of processed leaf possesses its own distinctive color, aroma, and flavor. But overall, green tea leaves tend to be dark green, the liquor crystalline, green with a yellowish tint, and the aroma, fragrant and refreshing.

Although the production process for Green Tea is relatively the most simple, of all tea types of green tea are the most difficult to brew due to the difficulty of getting the water temperature just right.

Because the raw materials for green tea are tender tips and immature leaves, the temperature of the water used for brewing must absolutely not be too high; overly hot water not only kills some nutrients and minerals in the tea, but also renders the liquor bitter, and robs the flavor of its vitality.

Generally speaking, a temperature of eighty degrees centigrade is appropriate for infusing green tea, but when actually brewing one should take the state of the tea leaves into consideration in deciding the specific temperature. The maturity of the leaves is the principal element to consider: more tender leaves call for a slightly lower temperature, while relatively mature ones require somewhat hotter water.

In a doubtless familiar vignette from our daily lives, green tea is often brewed within a slender and elegant glass cup without a lid. The biggest advantage of choosing glass as a receptacle for brewing tea is that you can directly observe how the leaves are transformed and the liquor takes on color.

Glass is the preferred choice, but it is not the sole option. Whether you seek a bit of charm or wish to display the liquor, a lidded eggshell porcelain cup (tureen) fittingly highlights the temperament of green tea. In short, in order to accentuate the fresh and invigorating disposition of green tea, for teaware, one should select high-density materials that dissipate heat rapidly. By such a standard, silverware is an excellent choice.

Yixing clay teaware, also known as “Red Porcelain” due to the color of the clay found only in Yixing (Jiangsu), is the most widely used teaware for Chinese tea. Compared to common porcelain, Yixing clay is quite porous and features very low density and relatively slow heat dissipation.

If green tea is brewed in a Yixing clay teapot, however, the resultant liquor will give off a rather odd, somewhat dank, smell. The aroma reminds one of the springtimes in northern China which is somehow never as refreshing or cheerful as in the south.

This shows just how great the choice of teaware impacts the taste of the tea. Of course, the shape of the vessel also has an impact on the quality of the tea liquor. For example, the opening at the top of a typical Yixing teapot is not as large as that on a porcelain tureen, and this will also have an effect on the green tea liquor.

DRAGON WELL (Green Tea), 龙井)

Ancient Chinese poetry often likened Hangzhou’s West Lake to Xishi, one of the four most well-known beauties in the history of China. And it is in the vicinity of West Lake, with its enchanting mist-covered scenery interspersed with brooks, that tea leaves rivaling her beauty were first produced - Dragon Well.

Dragon Well Tea has a long history, but the roots of its fame go back to the reign of Emperor Qianlong of the Longjing tea, who loved to leave the capital in Beijing to travel in South China, particularly the region to the south of the Yangtze River that straddles today's Shanghai and parts of Zhejiang and Jiangsu.

The tea takes its name from a well. Legend has it that this well did not dry up even during long droughts, and people believed it to be the lair of the “Dragon that Rules the Seas,” hence the name, "Dragon Well". It is said that the Qing Dynasty for "Dragon Well,” still visible today, were inscribed on the outer wall of the well by none other than Emperor Qianlong himself, a fact that evokes a sense of nostalgia among some visitors.

Intriguingly, from older times up until today, water drawn from the Dragon Well has not just been used for steeping tea. When locals find themselves at a disadvantage in a game of mahjong, they dip their hands in Dragon Well water and apply it to their face, forehead, and hair while praying for protection and good luck. Evidently, Dragon Well has become a cultural and folkloric symbol with great significance.

Dragon Well Tea has long had a reputation for its “Four Perfections”: “jade hue, sweet scent, mellow flavor, pleasing shape." The first three are references to the liquor, while the last refers to the appearance of the tea leaves. In fact, such a description is arguably applicable to most other green tea. Nonetheless, each variety of green tea leaf does possess its own unique temperament that constitutes a recognizable point of difference.

If we disregard the human factor represented by the tea master and his or her 'team and restrict ourselves just to the tea leaves, then the quality of Dragon Well is decided by three key elements.

The first decisive element is the specific location of the tea farm. The environment in this location dictates that the Lion Peak sub-region grows the finest Dragon Well.

The second decisive factor is exactly when the tea is harvested. The optimal period is in the ten days before the Chinese characters in early April, and the next best is after Qingming but before the spring rains. Locals reflect the order of the harvest in the names given to each: “Daughter’s Tea," “Wife’s Tea” and "Mother-in-law’s Tea.” We need to note that the custom of grading and naming tea according to its harvest time is not restricted to Dragon Well.

The third decisive factor is the relative tenderness of the leaves. “Lotus Heart” Dragon Well is composed of just buds. “Banner Spear” consists of a single bud and a single leaf; the bud is tightly wrapped like a spear but expands like a banner when brewed. And the graphic “Bird’s Tongue” comprises a single bud plus two leaves. These three appellations are easily pictured in the mind and memory. When brewed, water temperature should be lowest for Lotus Heart, since it is the most delicate, warmer for Banner Spear, and hottest for Bird’s Tongue.

Because the output of Lotus Heart is extremely limited, its price is very high. Most people buy the tea to present as a gift with frankly utilitarian intent. It is satirically referred to as “flattery tea,” an allusion to the popular practice in today’s China of making a substantial gift as a shortcut to material or professional success.

One thinks too of ancient China when the relationship between tea and men of letters was an intimate one. Besides making a gift of spring tea, much attention was also paid to presenting “a sprinkling of the finest tea leaves,” because the best tea was produced in very limited amounts, and therefore quality trumped quantity.

Besides the characters for "Dragon Well” inscribed in the emperor's own evocative calligraphy, the presence of “Tiger Running Spring” near the Dragon Well and the shores of West Lake adds not a little legendary color to Qingming Festival. Tiger Running Stream and Dragon Well Tea are known as the perfect duo of West Lake. Infusing Dragon Well with water drawn from Tiger Running Spring is the combination of two of the finest things here on the earth.

To brew

a pot of Dragon Well by the shores of West Lake ranks as a marvelous occasion

in the life of a mortal. Having attained this acme, could one ask for more?

GREEN SPIRAL 碧螺春

No matter where he or she was born in the country, each Chinese has an inexplicable attachment to the area of South China. This sentiment has come down to us over a millennium, shrouded in a magical, impenetrable fog. The a famous saying in praise of the ancient sister cities in South China, "Paradise above in heaven, Suzhou, and Hangzhou below on earth,” captures the legends that surround the region. If Hangzhou, this paradise on earth, is made more colorful by Dragon Well Tea, then a similarly fine reputation is attached to a famous tea from Suzhou - Green Spiral.

Green Spiral is cultivated within the East and West Dongting Mountains in Taihu Lake, China’s third-largest freshwater lake is dotted with ninety islands. Mist-covered mountains and waters intermingle here in an ethereal locality that has engendered many distinguished talents over the centuries.

What makes the Green Spiral plantations even more unique is the way the tea plants are planted among various types of fruit trees. The tall fruit trees shade the tea bushes in the summer and protect them from frost in the winter. Their roots and leaves intertwine like intimate lovers, scenting the tea leaves with a delightful fruity aroma.

Unlike Dragon Well Tea that is named for the place where it is grown and produced, the name Green Spiral neatly captures its color, shape and invigorating spring flavor.

The razor-thin Dragon Well leaves are shaped like the blade of a sword, while Green Spiral leaves are fine and curled and covered in tender white hairs. The amount of such fur on the underside of the tender bud is the indicator by which the “tenderness” (age) of the tea is determined.

Interestingly, like Green Spiral, Dragon Well is also very tender, but during production, those baby white hairs are rolled inward, effectively concealing them. The fact that the white fuzz is less evident to the eye does not mean that Dragon Well is necessarily less tender than Green Spiral.

The aroma of Dragon Well is as limpid as a feather-weight youth testing his mettle for the first time, or a new-born calf naively uncowed by a tiger, and its the fragrance is accompanied by a subtle chill. In contrast, the flavor of Green Spiral resembles a coquettish young maiden awaiting betrothal, and thus likely to engender affection.

Green

Spiral can be brewed at the same temperature as Dragon Well, or even slightly

lower. But due to factors such as the way it is rolled, Green Spiral releases

its essential flavor and ingredients much faster than Dragon Well, and

therefore its steeping time is considerably shorter than Dragon Well’s.

MOUNT MENG SWEET DEW 蒙顶甘露

In an industry that is naturally classified by region of cultivation, Sichuan's share of China's tea market is hardly outstanding. It hasn’t the means to compete with the green tea of the Yangtze River basin, nor is it fit to joust with the likes of Fujian’s Oolong. But the historical import and unique temperament of Sichuan is irreplaceable and thought-provoking.

"Taxing is the roads of Shu, even more, taxing than ascending the heavens.” Thus wrote Li Bai, one of China’s greatest poets, about Shu (modern-day Sichuan) back in the eighth century. These remain the basic geographical traits of Sichuan - overlapping sierras, endless crags, natural barriers, and many famous mountains. Of course, famous tea flourishes amidst famous mountains. In these forested mountains covered in cloud and mist, water vapor lingers throughout the day, and there is a wealth of vegetation and animals. This is the sole place in China where the geography and environment permit the air, rain, and dew to float about so divinely, endowing Sichuan tea with their unique spirituality.

Mount E’mei is the most beautiful under the sky and Mount Qingchcng the most secluded, goes an ancient Chinese saying. These two mountains have been famous for tea cultivation since ancient times, but among varieties of Sichuan tea, the Meng Mountain is the undisputed sovereign in historical terms. Mentioning tea of Mount Meng, a famous phrase comes to mind: "Like the waters of the Yangtze River is the tea on Mount Meng."

In fact, Mount Meng was not only an imperial tribute tea (for presentation to the emperor and nobility) over the centuries like Dragon Well and Green Spiral, it is also the first tea to be cited in ancient documents extant today. Furthermore, the earliest documentation of managed cultivation of tea bushes by ancient Chinese also refers specifically to Mount Meng tea. Evidently, Mount Meng tea has imbibed the rain and dew here over a millennium, it long ago fused harmoniously with mountains and the forests.

Since ancient times when Mount Meng tea was classified as a tribute item, it has been processed into various types of finished tea, but Mount Meng Sweet Dew (Mengding Gan Lu) currently enjoys the greatest popularity and widest dissemination. After processing and rolling, finished Mount Meng Sweet Dew is similar in appearance to Green Spiral, both being tightly curled and covered in fine hairs, or silver pekoe. But the former possesses a unique aftertaste true to its name: “sweet dew”, refreshing deep down with its mellow, blissful liquor.

The leaves plucked for Mount Meng Sweet Dew are no less tender than those of Green Spiral. Because both are so tender, when brewing either tea, “topping” is widely preferred among the common people, a reference to the practice of first pouring hot water into the teapot, and then adding the tea leaves on top. This method allows a “buffer” period between the time when the water is added and when the tea leaves are added, effectively lowering the actual water temperature at steeping. Since the tea leaves enter the water from the top, the leaves are not subjected to water pressure and the subsequent violent collision between the leaves and the inside of the teapot.

When brewing Mount Meng Sweet Dew, factors such as choice of utensils, water temperature, the number of tea leaves and the timing of each infusion can mirror those for Green Spiral, but adjustments can be made as desired.

Besides Sweet Dew, since ancient times the Mount Meng tea “family” has also included another star offspring: Mount Meng Yellow Bud (Mengding Huang Ya). Only buds are used, and it classifies as a yellow, not a green, tea. Yellow and green tea processing is similar, but the former undergoes a stage when water is added and the tea leaves are baked in a closed container. Some oxidation occurs, resulting in yellowish leaves and liquor. Yellow tea is considered a non-mainstream tea, but since ancient times there has nonetheless been no shortage of famous ones such as Mount Meng Yellow Buds.

It should be noted Yellow Bud is rolled quite differently from Sweet Dew. The former is more heavily rolled, resulting in tea leaves that are flat and uniform. Besides Mount Meng Yellow Bud, other famous Chinese yellow tea includes Junshan Silver Needle (Junshan Yin Zhen), Huoshan Yellow Bud (Huoshan Huang Ya), and Beikang Mao Jian.

Mengding

District is located within the disaster zone of the 5.12 Sichuan Earthquake in

2008. Originating in the region that underwent the historic changes wrought by

that series of destructive tremors, Sichuan tea has taken on a new association

that is a bit difficult to describe. But Mount Meng Sweet Dew now seems more

precious, each tea leaf richer in sentiment.

BAMBOO LEAVES GREEN 竹叶青

The role of bamboo in Dragon Well Tea and the life of the Chinese people have an incomparable significance and its impact has also deeply penetrated Japanese culture and even radiated throughout much of Asia.

And it is arguably due to scenes of bamboo groves in Southwest China - showcased in Ang Lee’s "Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon" - that the majority of Westerners have recently acquired a certain level of appreciation for China’s "bamboo culture." But in actuality, the importance of bamboo to the Chinese is far deeper than this.

Prior to the appearance of papermaking technology, Chinese culture had always been written on bamboo strips. In other words, bamboo was the medium for the recording of Chinas earliest civilization and history and has been a constant theme of poetry, painting, and calligraphy executed by literati and poets. Bamboo leaves boiled in water, bamboo shoots in food, utensils made of bamboo, sculptures carved from bamboo poles — bamboo is not only a link between antiquity and today, but it is also virtually interwoven into every layer of the life of the Chinese people.

“A diet without meat is preferable to daily life without bamboo.” In Southwest China, particularly the land occupied by the ancient State of Shu (modern Sichuan), a swathe of green bamboo typically encircles a hamlet, a popular “landscaping” tradition that has carried on for a millennium. Each famous mountain in Sichuan boasts its own endless sea of myriad “spears and banners” comprised of jutting bamboo poles and legions of leaves.

Bamboo branches dip much like a maiden's eyelids lowered out of shyness, or the kind demeanor of a modest gentleman. People adore the constant jade-green of bamboo throughout the four seasons, and thus the appellation Bamboo Leaves Green (Zhu Ye Qing) is much beloved. Besides being the name of the tea featured in this chapter, it is also the name of a Sichuan liquor and the name of a snake often seen in South China.

Though both are Sichuan tea, the name Bamboo Leaves Green has existed for less than half a century, and seemingly cannot be uttered in the same breath as Mount Meng tea. But that does not signify that tea production in Mount E’mei lacks history or that the moniker Bamboo Leaves Green lacks cachet. Tea is grown in Mount E’mei was classified as an imperial tribute as early as the Chinese characters. Although its formulation occurred fairly late, Bamboo Leaves Green was christened by General Chen Yi, and thus its appellation is not without legendary color.

The superbly beautiful Mount E’mei has its own forests of verdant bamboo, and this means the tea leaves grown there cannot but absorb some of the characteristics of bamboo. The name Bamboo Leaves Green, like Green Spiral, also serves to illustrate the teas shape, color, and flavor. The processed tea leaves are long strips, tapered at both ends and fuller in the middle, and shaped like bamboo leaves. When infused they hang in the liquid-like needles suspended in mid-air. The leaves are bamboo green, and the liquor is pale jade as if dyed with bamboo leaves. Its aroma and flavor emulate a bamboo leaf’s temperament, that is, slightly bitter with a sweet aftertaste.

If we examine it more closely, the flavor of Bamboo Leaves Green has intriguing connotations of tea and Zen (Chan in Chinese). Before Bamboo Leaves Green was formally named, it had long been grown and produced by monks at Mount E’mei Ten Thousand-Year Temple and Buddhist monasteries in the vicinity. It was reserved for imbibing during meditation.

Compared to the bracing coolness of Dragon Well’s aroma or the delicate aroma of Green Spiral, if infused with equally hot water, Bamboo Leaves Green’s aroma is not so pronounced. From the very first taste, that is almost void of aroma, until the tea liquor has entered the throat and a long-lasting and charming aftertaste becomes apparent, only someone in a tranquil and controlled frame of the mind can experience it fully.

While it is a young and vibrant green tea, Bamboo Leaves Green also possesses a sense of detachment, bamboo-like integrity, and understated inner strength. This tea is like an exceptional child who, when others are jumping with joy, lags just a bit behind.

Tea-tasting

is an act of meditation - and this is the genuine taste of Bambook Leaves

Green.

Responses • 0

0/2000

ID: 322

Matthias

Offline

Oct 10

Visited

From

Hafizabad, Pakistan

Send Message

Related

Every one have any teacher book of Easy step to Chinese 4. Can share me some file for free download.言他人易守己身难 #chinese #idoms #hsk #xiaolinchineseteaching - YoutubeI uploaded "Authentic Materials for Chinese Teaching and Learning", enjoy it.

https://www.cchatty.com/pdf/4018new sheet for teaching chinese letters“开弓没有回头箭” #chinese #idioms #hsk #xiaolinchineseteaching - YoutubeIt is fun to be a Chinese teacher to teach my native language to the non-Chinese speakers. There are a lot words and expressions, which have been used without any second-thoughts, astonish me from time to time. For example, "有点儿“and "一点儿”, it has never occurred to me that "有点儿“ expresses a tone of unsatisfactory. "怎么走“和“怎么去”, one is to ask about the route and one is to ask the manner of transportation.

At the same time, it is also fun to see that students from all over the world are fascinated in the long Chinese history and the unique pictograph Chinese Characters.

Someone says Chinese is difficult, however there are still many "foreigners" who can speak very proficient Chinese. It is up to the persistence and perseverance.I uploaded "Teach Yourself Chinese", enjoy it.

https://www.cchatty.com/pdf/3103Does anyone have all past papers for HSK 3? If yes, then let me know, as I have an exam on the 12th of April, and I'm facing a problem while downloading..I really appreciate any help you can provide..Nihao. Where can i find the mock test for HSKK? Complete answer written in English because i can’t read the chinese character? Xiexie.I uploaded "Teaching Chinese Mock Test 1", enjoy it.

https://www.cchatty.com/pdf/3190